The Administration of Moderate and Deep Sedation: Legal, Ethical Issues for Non-Anesthetist RNs

By Michael R. Eslinger, CRNA, APN, MA

The advent of same day surgery centers and the rise in office based procedures requiring moderate sedation rose dramatically in the 1980s and continues at a rapid pace today. Determining what constitutes sedation and what constitutes anesthesia has created political, legal and ethical dilemmas among anesthesia providers and physicians over determination of the patient’s ASA status, the drugs used for sedation, and critical patient safety considerations that arise across a wide variety of clinical settings. Many states and nursing organizations continue to take a passive role in the oversight of sedation activities attended by registered nurses, while some organizations such as the Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN), Society Of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (SGNA), and the American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses (AAMSN) currently offer guidelines, resources and training for nurses who have had no additional training to attend to a wider range of clinical sedation scenarios.

The Joint Commission for Health Care Organizations (Joint Commission) defines moderate sedation or conscious sedation as a minimally depressed level of consciousness induced by the administration of pharmacologic agents in which the patient retains continuous and independent ability to maintain protective reflexes, a patent airway and can be aroused by physical or verbal stimulation.1

The intention of Sedation Certification, in its obligation to administer safe sedation, was not to develop an ANCC National Certification, but to offer a program that did offer a Sedation Certification which certifies that all standards and policies set by all Accreditation Organizations for Health Care facilities, which include the following conscious sedation accrediting organization. They include the Joint Commission for Health Care Organizations, the National Intergraded Accreditation for Health Care Organizations (NIAHO) in affiliation with Det Norske Ventas (DNV), the Health Care Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC), and the Healthcare Facility Accreditation Program (HFAP).

The Joint Commission also states, each organization is free to define how it will determine individuals are qualified to administer patient sedation. Training recommendations given by the Joint Commission include, but are not limited to, ACLS certification, a satisfactory score on a written examination, and a mock rescue exercise evaluated by an anesthesiologist. With regard to non-Licensed Independent Providers (non LIPs), such as nurses, who are permitted to administer the sedation, the permission could be found in the individual’s job description, or other documentation in their personnel file.1

Nursing personnel are consistently involved with ongoing management of patients receiving sedative or analgesic medications during invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Medication administration, patient monitoring, discharge instruction, and family teaching are among the primary patient safety concerns. All are care elements performed directly by the nurse. State boards of nursing define scope of practice with varying degrees of specificity. It is nonetheless, the sole legal responsibility of each nurse to be fully familiar with the policies and guidelines of their state’s board of nursing, independent of the wide variation of clinical settings in which moderate sedation is administered. Such settings include diagnostic/interventional radiology/cardiology settings, dental and oral surgery centers, free standing endoscopy centers, emergency room settings, plastic surgery centers, and other outpatient settings that may or may not be associated with, or located within an acute care facility.

Sedation, moderate sedation, I.V. sedation, conscious sedation and sedation/analgesia are used interchangeably. Benzodiazepines and narcotics are the most frequently used drugs for sedation. Procedural sedation is most often associated with deep sedation using anesthesia class medications such as propofol or ketamine and involving pediatrics. However, state boards of nursing, health care institutions, medical and nursing organizations have developed their own position statements concerning the administration of anesthesia class medications. Their intent is the use of anesthesia medications such as propofol for moderate sedation. The FDA packaging directions for anesthesia class drugs and the training required to administer them is very specific, but ignored by some states and some medical associations.1 Nurses are asked to give these drugs against the package insert.

The AAMSN lists the registered nurse’s responsibilities in sedation related procedures to include: being aware of their state board of nursing and their facility position statement regarding RNs giving sedation, understanding the goals of moderate sedation, differentiating between moderate and deep sedation, being knowledgeable about the medications used, knowing the side effects and unplanned outcomes, as well as performing ongoing assessment of the patient, recognizing arrhythmias, using and interpreting pulse oximetry, and being able to intervene appropriately when oxygenation levels drop. The sedation nurse must also ensure the appropriate monitoring equipment is available and functioning properly, verify the informed consent has been signed by the patient prior to sedation, and the patient will be accompanied by a responsible adult upon discharge. It is also the responsibility of the nurse to participate in performance improvement activities.2

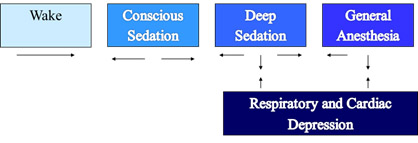

The Joint Commission states, the person administering the medication must be qualified to manage the patient at whatever level of sedation or anesthesia is reached, intentionally or unintentionally. The figure below depicts the continuum of care which describes the patient’s level of consciousness from the waking state to general anesthesia. The arrows indicate the different outcomes that can occur at each level along the continuum.3

Figure 1 Continuum of Care

The nurse has the responsibility within the continuum of care to do the following:

- Evaluate patients prior to moderate or deep sedation.

- Rescue patients who slip into a “deeper than desired” level of sedation or anesthesia.

- Manage a compromised airway during a procedure.

- Handle a compromised cardiovascular system during a procedure.

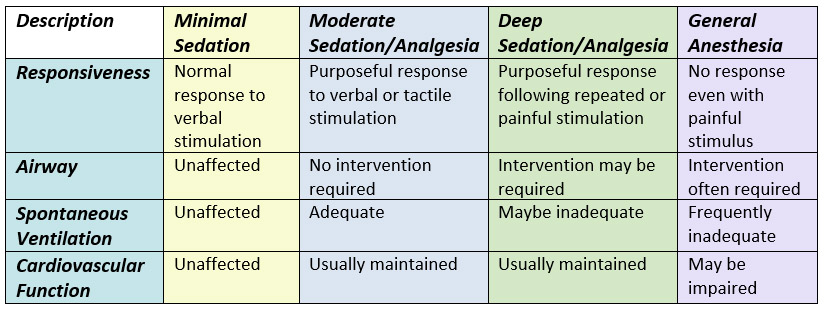

Figure 2 gives a list of the identifying characteristics within the continuum of care. 4

Figure 2 Identifying Characteristics for Continuum of Care

The Joint Commission Anesthesia/Sedation healthcare standards further require that individuals who are approved to administer any type of sedation are able to perform airway and cardiac rescue. It is well recognized that registered nurses trained and experienced in critical care, emergency and/or peri-anesthesia specialty areas may be given the responsibility of administration and maintenance of sedation in the presence, and by the order of a physician who is present during the procedure. Although, the ultimate responsibility for the care of the patient lies with the procedural physician, the registered nurse must have the knowledge, skills and experience to assess, interpret and intervene in the event of a range of complications. Even though, such nurses are Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) certified and trained in the ability to resuscitate, they are not legally recognized to administer or monitor patients under general anesthesia.5

Among the legal issues confronting nurses is the lack of a detailed sedation policy by some state boards of nursing. There are currently ten states that do not have a sedation policy for non-anesthesia nurses. Therefore no guidelines exist for moderate sedation in those states other than what the facilities or practices themselves develop. Of equal concern, is the administration of sedation to geriatric and pediatric age specific populations with varying comorbidities or risk factors.6

ACLS certification is not a Joint Commission requirement, but is used as an example for institutions to use as a certification requirement.7 Therefore, in a state which does not require ACLS certification it is possible for a patient to receive sedation from a nurse who is not ACLS certified. For example, the American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses (AAMSN) was contacted recently by a new nurse hire concerned that the only orientation to sedation she received was a four page printout with no guidance or policy regarding sedation other than drug dosages and sedation definitions. Current Basic Life Support (BLS) certification was the only recomendation.8

Another recent example was an advertisement in a Texas newspaper to hire a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) to administer and monitor office sedation. The Texas Board of Nursing specifically states, the administration of pharmacologic agents via I.V., or other routes for the purpose of achieving moderate sedation requires mastery of complex nursing knowledge, advanced skills, and the ability to make independent nursing judgments during an unstable and unpredictable period for the patient. It is the opinion of the Board that the one-year vocational nursing program does not provide the Licensed Vocational Nurse (LVN/LPN) with the educational foundation to assure patient safety or to achieve optimal anesthesia (sedation) care.9 Any LPN taking position as sedation nurse in Texas would be putting his/her license in jeopardy and expose themselves to possible legal actions, as would the physician group hiring the LPN.

However, the Oregon State Board of Nursing in 2006 adopted the position that it is within the scope of practice for the Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN), Registered Nurse (RN), Nurse Practitioner (NP) and the Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) to administer sedating agents for the purpose of anxiolysis.10 The Joint Commission standards for sedation and anesthesia care do not require the granting of privileges for the administration of minimal sedation (anxiolysis). Both minimally and moderate sedated patients continue to respond normally to verbal commands, and they demonstrate normal cardiovascular ventilatory function, although their cognitive function and coordination may be impaired. An often asked question is; does the minimally sedated patient’s sedation nurse have to meet the same standard of training as the RN doing moderate sedation? By definition no, however, when considering the continuum of care and the requirement that the sedation nurse must be able to rescue one level deeper, whether by intent or by accident the minimal sedation nurse would be responsible for meeting the same requirement as the moderate sedation nurse.11

There are ten state Boards of Nursing that have no policy concerning nurses giving sedation and still others that refer the responsibility to the institution. With significant numbers of same day surgeries, endoscopy clinics, radiology, dental and office based surgeries that are not governed by the standards set by the accreditation organizations; patient safety and liability considerations are of prominent concern. If a facility is not accredited, and without state board of nursing standards the only guidelines are those created by the institution, or based on the limited nursing scope of practice for that state.12

The legal and ethical controversies for non-anesthesia RNs giving sedation is a concern with both the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists and the American Society of Anesthesiologists mainly due to the introduction of midazolam as a sedation agent, which was responsible for 83 reported deaths due to the lack of adequate practitioner training.13

Concern in the early 1990s that non-anesthesia nurses giving sedation would evolve into untrained anesthesia providers giving anesthesia classified medications continues to be a controversial issue. One of the reasons cited for this is problematic insurance reimbursement to anesthesia providers for episodes of moderate sedation, compounded by a shortage of anesthesia LIPs needed to cover the increasing number of non-hospital institutions administering moderate/deep sedation to their patients.14 That need, increased the use of non-anesthesia nurses giving and monitoring moderate sedation.

Anesthesia Medications

The two most controversial anesthetic medications given by non-anesthesia providers are propofol and ketamine. Ketamine is most often used in the emergency department for pediatric deep sedation and is not addressed in this article.

Propofol, a general anesthetic, was introduced into anesthesia practice in the early 1990’s, raising legal and ethical issues related to non-anesthesia nurses administering drugs previously classed as anesthetics.14 Propofol was used exclusively for general anesthesia or monitored anesthesia care (MAC) sedation, and administered only by persons trained in the administration of general anesthesia. More importantly, the administering clinician was not involved in the conduct of the surgical/diagnostic procedure, but was only responsible for the continuous monitoring of the patient’s status, for maintenance of a patent airway, for artificial ventilation, oxygen enrichment and for circulatory resuscitation if necessary.

Administration of propofol for sedation by non-anesthesia trained providers is clouded in controversy. Customarily, sedation for outpatient procedures has been performed using a benzodiazepine and opioid combination. While the benzodiazepine and opioid combination remains the most frequent choice, the use of propofol for sedation is increasing. Nurse-Administered Propofol Sedation (NAPS) is “The administration of propofol by a registered nurse under the direction of a physician who has not been trained as an anesthesiologist.” The target level is deep sedation.15

The Nurse’s role15

- Administration of propofol through physician ordered titration and patient monitoring

- Need to anticipate portions of the procedure that may be more painful or stimulation in order to anticipate the need for more sedation

- Vigilant monitoring of the airway

- Continuous monitoring of respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate, oxygenation status and end tidal carbon dioxide level

- NAPS is intended as a monotherapy (the use of one medication)

Current concern from both ASA and AANA, advise that propofol can compromise a patient’s airway, potentiate undesirable cardiovascular events, and no reversal agent is available for propofol, resulting in recommendations that non-anesthesia providers should not administer the drug. The non-anesthesia providers who advocate the use of propofol for sedation argue the off label use and the short duration of effect which makes the use of a reversal agent unnecessary. The argument is that the metabolizing of propofol is faster than an anesthesia provider can prepare, give and wait for the effect of a reversal agent to take place. Another argument is the number of propofol sedation’s given without documentation of life-threatening adverse outcomes. RNs giving propofol for sedation must ask themselves if they are prepared to manage the following possible adverse effects:

- Respiratory depression, apnea, hiccup, bronchospasm, laryngospasm

- Cardiovascular effects –hypotension, arrhythmia, tachycardia, bradycardia, hypertension

- CNS effects – headache, dizziness, euphoria, myoclonic/clonic movement, seizures, and sexual illusions.

Due to the importance assigned to the task of monitoring the patient receiving sedation, a second nurse or associate is required to assist the physician with those procedures that are complicated either by the severity of the patient’s illness and/or the complex technical requirements associated with advanced diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

During the administration of propofol, patients should be monitored without interruption to assess level of consciousness, and to identify early signs of hypotension, bradycardia, apnea, airway obstruction and/or oxygen desaturation. Ventilation, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure should be monitored at regular and frequent intervals. Monitoring for the presence of exhaled carbon dioxide should be utilized unless invalidated by the nature of the patient, procedure or equipment. Movement of the chest will not dependably identify airway obstruction or apnea.

Further, the practitioner administering propofol for sedation/anesthesia should, at a minimum, have the education and training to identify and manage the airway and cardiovascular changes which occur in a patient who enters a state of general anesthesia, as well as the ability to assist in the management of complications.16

The FDA has approved the use of Computer-Assisted Personalized Sedation (CAPS) devices which seek to make the delivery of propofol sedation predictable, precise, and safer by using computer algorithms to calculate and deliver appropriate amounts of propofol, based on quantifiable physiological parameters. Physiological patient data (i.e., oxygen saturation, capnometry, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, electrocardiography, and patient responsiveness) are monitored continuously by CAPS devices. The device processes the data using a computerized drug delivery algorithm, and is able to titrate sedation by varying the propofol infusion and administering boluses of propofol. The use of CAPS does not preclude the use of a qualified sedation nurse.17

ASA physical classification

Use of sedation outside the main operating room is intended for either patients with no illness or those with minimal illness. Before undergoing sedation, all patients are assessed by the physician and nurse performing sedation using the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status System.18 This system helps qualify relative risk to patient’s sedative medications. The higher the level of classification the more the health care team must be alert for possible complications of sedation.

The ASA classification can be controversial when gray areas are misinterpreted or purposely downgraded to lean toward sedation rather than anesthesia. The six ASA classifications are:

ASA I: Normal healthy adult

ASA II: Mild systemic disease

ASA III: Severe systemic disease with functional limitation that is not incapacitating.

ASA IV: Severe systemic disease that is a life threating

ASA V: A patient not expected to survive more than 24 hours without surgical intervention.

ASA VI: Declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes

Pre-procedure preparation is not complete until rapport has been established with the patient and the informed consent is signed and witnessed. Through patient assessment and interview the nurse can determine the patient’s expectations and can give assurance in any area where the patient shows concerns. Getting an I.V. access, EKG/blood pressure and pulse oximetry applied are required for all patients. Protocol requires that all equipment is checked and made available and medications are prepared. The patient’s airway is then evaluated.19

Airway

The pre-sedation assessment is both a physician and nursing responsibility and includes establishing NPO status, chief complaint, current medications, drug allergies, ancillary studies, airway evaluation, history of substance abuse or sleep apnea, medical/surgical history, concurrent medical problems, ASA status, communication ability and physical exam. Each of these is self-explanatory and there should be no question as to their importance.

As an illustration of the importance of the above elements in a pre-sedation assessment, there may be other missed opportunities besides procedure related efficacy. A case involving a patient complaining of difficulty swallowing and epigastric discomfort was scheduled for an Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). The sedation nurse was a RN. The primary complaint of difficulty swallowing was ignored by the physician, admitting nurse and the sedation nurse. Secondarily, the patient also stated he was very sensitive to midazolam and had prolonged deep sedation in the past. He requested they start with one fourth of the normal dose. When injected with the sedation analgesia medications, he asked, “What did you just give me?” The nurse stated that she had given him 2 mg of midazolam and 50 µg of fentanyl. Despite his informing the nurse about his sensitivity the patient was given their standard medication dosage. As a result he experienced over 48 hours of amnesia. The diagnosis after endoscopy was negative for epigastric problems and no reason was given for his difficulty swallowing. Unfortunately several months later it was discovered that he had a cancerous tumor on the base of his tongue the size of a ping pong ball. The physician never saw the tumor during the EGD.

That patient was lucky, and the staff that did the endoscopy were also very fortunate that he did not have any respiratory difficulty. But the excessive dose of midazolam in conjunction with the large tongue tumor could have been disastrous.

Lesson: A simple airway exam can mean the difference between safe sedation or a procedural nightmare.

Managing the airway is the most crucial and controversial issue in non-anesthesia nurse sedation. An adequate evaluation of the airway is crucial. It is non-invasive and can be quickly completed with simple observation. The LEMON mnemonic contains the following observations for patient assessment:20

- Look externally

- Evaluate the 3-3-2 rule: Open mouth 3-fingers width, chin to hyoid bone 3-fingers, and hyoid bone to thyroid notch 2-fingers.

- Mallampati

- Obstruction

- Neck mobility

The lemon mnemonic should be included in every patient assessment.

Mallampati Airway Classification

The Mallampati classification is a well-established assessment tool and is easy to perform and entails no cost. It is considered an accurate predictor of subtle anatomic causes that could cause difficult intubation. To perform the assessment the patient should sit upright with the head in neutral position. The patient is then asked to open the mouth as wide as possible and to protrude the tongue as far as possible.

Classification can then be made as follows per visualization the anatomy listed below.21

Class I: Soft palate, uvula, anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars.

Class II: Soft palate, fauces, uvula

Class III: Soft palate, base of uvula

Class IV: Soft palate not visible at all.

Patients with Mallampati Class III and IV should have an anesthesia consultation prior to administration of moderate sedation. The literature has shown that the higher the assigned Mallampati classification, the higher the incidence of difficult intubation. The sedation nurse should also be aware of the patient’s cervical range of motion. Any restrictions with hyperextension of the head and neck, such as, arthritis can cause a lack of neck mobility which can affect the patient’s airway making intubation difficult.22 The nurse who uses the Mallampati classification may better understand the effectiveness of the head tilt, chin lift airway maneuver.

Conclusion

The issue of competency of the sedation nurse is based on three criteria. 1. Does the nurse have the knowledge, training, and experience to give safe and effective sedation? 2. Is the nurse comfortable and competent in maintaining the patient’s airway? 3. Is the nurse vigilant and able to recognize, prevent and/or treat possible adverse events? The above criteria can be based on the nurse’s experience. The nurse involved in giving sedation 3 to 5 days a week is much more competent and comfortable than the nurse in the sedation 3 to 5 times a month. Nurses who have no other responsibilities except for giving and monitoring sedation contribute to patient safety. Therefore, a second nurse or assistant is most often required to assist the physician with those procedures that are complicated either by the severity of the patient’s illness and/or the complex technical requirements associated with advanced diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

The registered nurse performing sedation must be knowledgeable and familiar with the RN scope of practice in their state, their institution’s guidelines, as well as the Joint Commission, AANA and ASA guidelines for patient monitoring, drug administration, and protocols for dealing with potential complications or emergency situations during and after sedation. The AAMSN scope of practice for non-anesthesia RN’s is another reference.23

References

- Kost, Michael, (1998), Moderate Sedation/Analgesia Core Competencies for Practice, Second Edition, Elsevier, St. Louis

- American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses, aamsn.org (2012)

- Smith, Dean F., (2001), Sedation, Anesthesia, & the THE JOINT COMMISSION, Second Edition, Opus, Marblehead

- American Society of Anesthesiologists article, March 2002 Volume 66, Number 3, Practice Management: Sedation and the Need for Anesthesia Personnel Karin Bierstein, J.D.

- Smith, Dean F., (2001), Sedation, Anesthesia, & the THE JOINT COMMISSION, Second Edition, Opus, Marblehead.

- Brustowicz, Krauss B. “Pediatric Procedural Sedation and Analgesia”, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland. (1999).

- Smith, Dean F., (2001), Sedation, Anesthesia, & the THE JOINT COMMISSION, Second Edition, Opus, Marblehead.p82

- Eslinger, Michael R. Personal phone conversation to Healthy Visions Sedation Certification. (2011).

- Texas State Board of Nursing http://www.bon.state.tx.us (2014)

- Oregon State Board of Nursing http://www.oregon.gov/OSBN/pdfs/policies/sedation.pdf (2006)

- Smith, Dean F., (2001), Sedation, Anesthesia, & the THE JOINT COMMISSION, Second Edition, Opus, Marblehead.p82

- com/resources/position-statements/position-statements-by-state/2014

- Sedation Analgesia: THE JOINT COMMISSION Requirements and How to Fulfill Them. Norah N. Naughton, M.D., Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Health System (2010).

- American Society of Anesthesiologists asahq.org (2012)

- Society for Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates sgna.org GINurseSedation/NAPSandCAPS.aspx (no date given)

- American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses, aamsn.org 2013

- gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DeviceApprovalsandClearance May 3, 2013

- American Society of Anesthesiologists, https://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm

- Odom-Forren, Jan and Donna Watson, Practical Guide to Moderate Sedation/Analgesia, Second Edition, Elsevier, St. Louis. (2005)

- E.M.O.N., www.youtube.com/watch?v=LEINTcbeVZ0 (2010)

- Mallampati http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mallampati_score (2014)

- Anesthesiology V75, No 6, Dec 1997

- American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses, aamsn.org (2012)